The season of pruning

It’s portfolio-cleaning season at LVMH.

The luxury giant, home to seventy-five Maisons and counting, is quietly doing what conglomerates rarely admit to doing: trimming the fat. After years of expansion and acquisitions, a cooling global market has forced the group to confront the uncomfortable truth that not every brand under its umbrella can grow forever.

For all the scale of Louis Vuitton, Dior, and Loewe, there are a few names that linger in the margins and today, we are focusing on Kenzo. Once the exuberant child of Paris fashion, today it feels like the orphaned asset in a family of billion-euro stars.

The brand that lost its roar

Founded in 1970 by Kenzo Takada, the house brought Japanese exuberance to a rigid Paris scene. When LVMH acquired it in 1993 for roughly $80 million, it inherited a label full of life and colour, but also one deeply dependent on the charisma of its founder. Takada’s departure in 1999 left a creative vacuum that successive designers have struggled to fill.

The 2000s under Antonio Marras flirted with poetic bohemia but failed to scale.

Then came the Humberto Leon and Carol Lim era (2011–2019), which injected streetwear adrenaline. Their Tiger sweatshirt went viral, accessories grew to nearly 30 percent of sales, and Kenzo suddenly felt young again. But the hype proved fleeting. When the Tiger faded, so did the growth.

Felipe Oliveira Baptista brought conceptual polish and sustainability talk in 2019, only to be derailed by the pandemic.

By 2021, LVMH handed the reins to Nigo — a bold play that re-anchored the brand in authentic Japanese streetwear culture. The move made perfect creative sense; commercially, it remains unproven.

Inside LVMH’s performance machine

LVMH’s business model leaves little room for passengers. Between 2018 and 2024, revenues almost doubled to €85 billion, driven by a ruthless focus on desirability and scale.

Yet even the group’s Fashion & Leather Goods division, its profit engine, reported a five-percent turnover decline last year. In moments like this, executive attention shifts toward the brands that deliver the highest return on capital. Every Maison must justify its seat at the table.

Kenzo doesn’t.

It’s also a generational outlier.

The average founding year across LVMH’s fashion Maisons is around 1926: nearly half a century before Kenzo’s own founding in 1970. Most of its peers were built in an entirely different era of craftsmanship and couture storytelling: Louis Vuitton in 1854, Loewe in 1846, Dior in 1947.

Within that pantheon, Kenzo is almost too modern to lean on heritage, yet too established to play the disruptor. It sits in a no-man’s land between the icons of old-world luxury and the insurgent newcomers redefining the market.

A rumour that never really went away

Back in 2010, whispers surfaced that LVMH had hired Crédit Agricole to explore a potential sale of Kenzo. The company declined to comment, but the fact that the rumour reached WWD spoke volumes.

Fifteen years on, the same logic still applies. When performance lags, LVMH doesn’t sentimentalise, it prunes. Christian Lacroix was sold in 2005; Donna Karan/DKNY followed in 2016 the Group divested its stake in Off-White in 2024, signaling a renewed willingness to prune.

Kenzo fits the same profile: strong legacy, inconsistent execution, minimal scale.

A brand out of sync with the algorithm

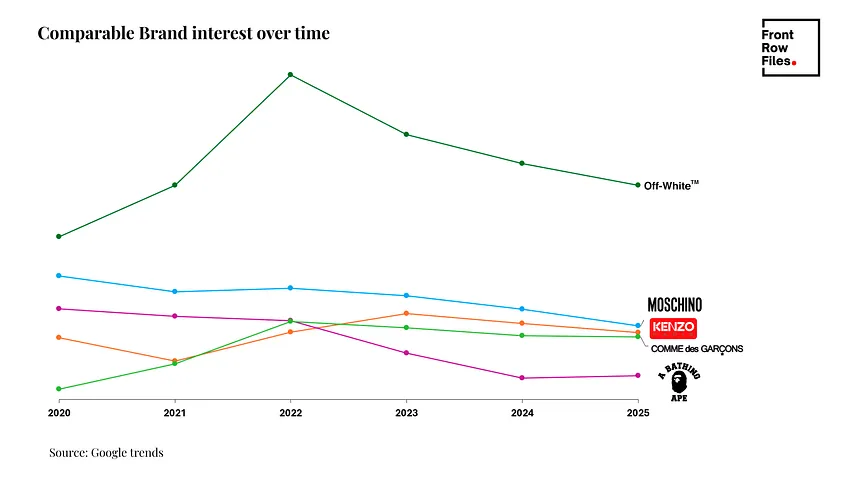

If cultural heat were measured in Google Trends, Kenzo would be tepid at best.

Search interest has been sliding steadily since the Tiger-hoodie peak.

Unlike Loewe, which turned artisanal craft into viral culture, or Givenchy, which keeps recalibrating its celebrity ecosystem, Kenzo hasn’t produced a conversation-shifting moment in years.

Online sentiment tells a similar story.

- “I’m thinking about buying one of them Kenzo Paris tiger print t-shirts but people are saying they’re associated with the wrong type of people.”

- “Good-looking sweaters, but extremely expensive.”

- “Decent sweaters but wouldn’t buy them even if reasonably priced.”

- “Loved it — roadmen ruined them, now I loathe that Tiger graphic.”

- “Tasteless. Can be flexed if you have no sense of style whatsoever.”

- “Dupes look almost identical and are dirt cheap.”

For a generation raised on Balenciaga shock tactics and Miu Miu’s quiet subversion, Kenzo feels stranded in the middle.

The Nigo opportunity and challenge

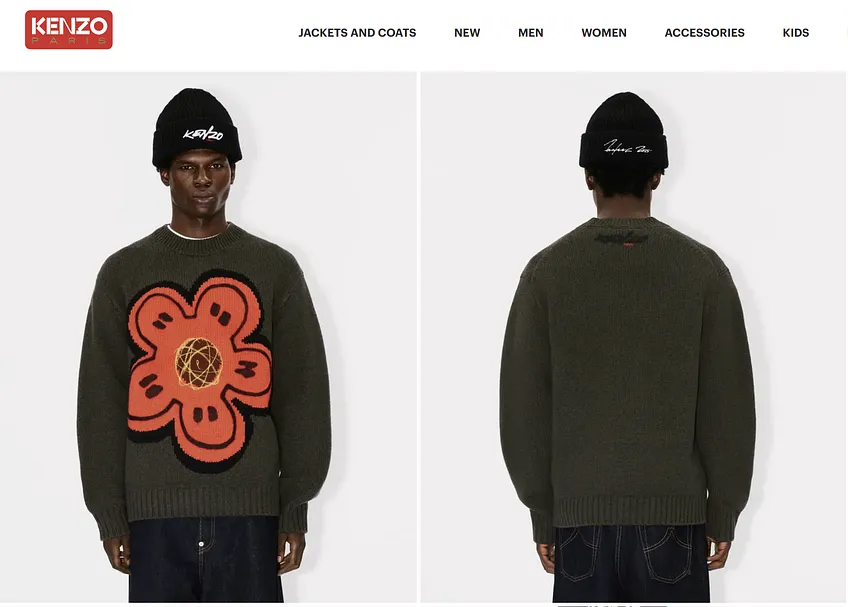

Bringing in Nigo, the Japanese designer who founded A Bathing Ape as creative director was a coup. He embodies the kind of cultural capital every luxury house craves: credible across streetwear, music, and art, yet disciplined enough to operate inside a conglomerate. His collections have toned down the logos, leaned into tailoring, and revived the Japanese boke flower as a new emblem. Critics generally saw this as a refinement.

The opportunity lies in authentic renewal.

Nigo’s vision taps directly into Kenzo’s roots: bold, cross-cultural, democratic, while rejecting the easy nostalgia of logos and archives. As he told Vogue Business, his goal isn’t to recreate “Japanese Kenzo” but to build a new culture that bridges Paris and Tokyo, tradition and futurism. It’s the most artistically coherent direction the brand has had in years.

If Kenzo’s current course fails to drive sustained growth in accessories and high-end ready-to-wear by 2026, even the best creative storytelling may not be enough to secure its place in the portfolio.

So who could be a suitable buyer?

If a sale happens, two pathways make sense.

1. The mid-market apparel route.

Think OTB Group (Diesel, Marni, Margiela) or a G-III-type buyer. They excel at licensing, wholesale, and scaling familiar names for the accessible-luxury market.

Kenzo’s global awareness and playful DNA would flourish in that environment.

2. The Asian luxury route.

An Itochu or Fast Retailing could view Kenzo as a ready-made bridge between East and West Japanese roots, Paris base, instant legitimacy.

With patient capital and a long-term Asia focus, Kenzo could finally find a home aligned with its heritage.

Either way, it’s clear the brand’s future value lies in volume and licensing, not in competing with Vuitton or Dior for couture credibility.

What happens next

Kenzo sits at a crossroads between creative renewal and commercial realism. After three reinventions in a decade, the brand’s challenge is not talent but traction.

Should LVMH choose to retain the brand, the mandate must be clear: deliver commercial traction, simplify the offer, and build from accessories up. Otherwise, the logical outcome is the same: a strategic divestment could unlock more value elsewhere.